I live close to a skate park and skate there often. I wanted to build a system that could detect how busy the skate park near me is without actually recording anyone or tracking anyone. Video was out of the question, and the device would only operate on audio without the audio even leaving the edge device. I wanted to show that machine learning can be anonymous and compress data so much that its original form no longer exists.

I built a system that analyzes half-second chunks of audio to detect whether there are skateboard sounds or not (specifically skate “pops”). The training method is pretty extensible to other forms of audio. It uses a 33-dimensional feature vector based on Fourier transforms.

Predicted data would be sent back from that device to my house a block away, and a website would be updated with the current state of the park. I shelved the project for now due to the difficulty of getting the solar power and battery capacity to run the power-hungry Teensy 4.1 I’m using. I’ll pick it back up someday if there’s interest.

Data Collection

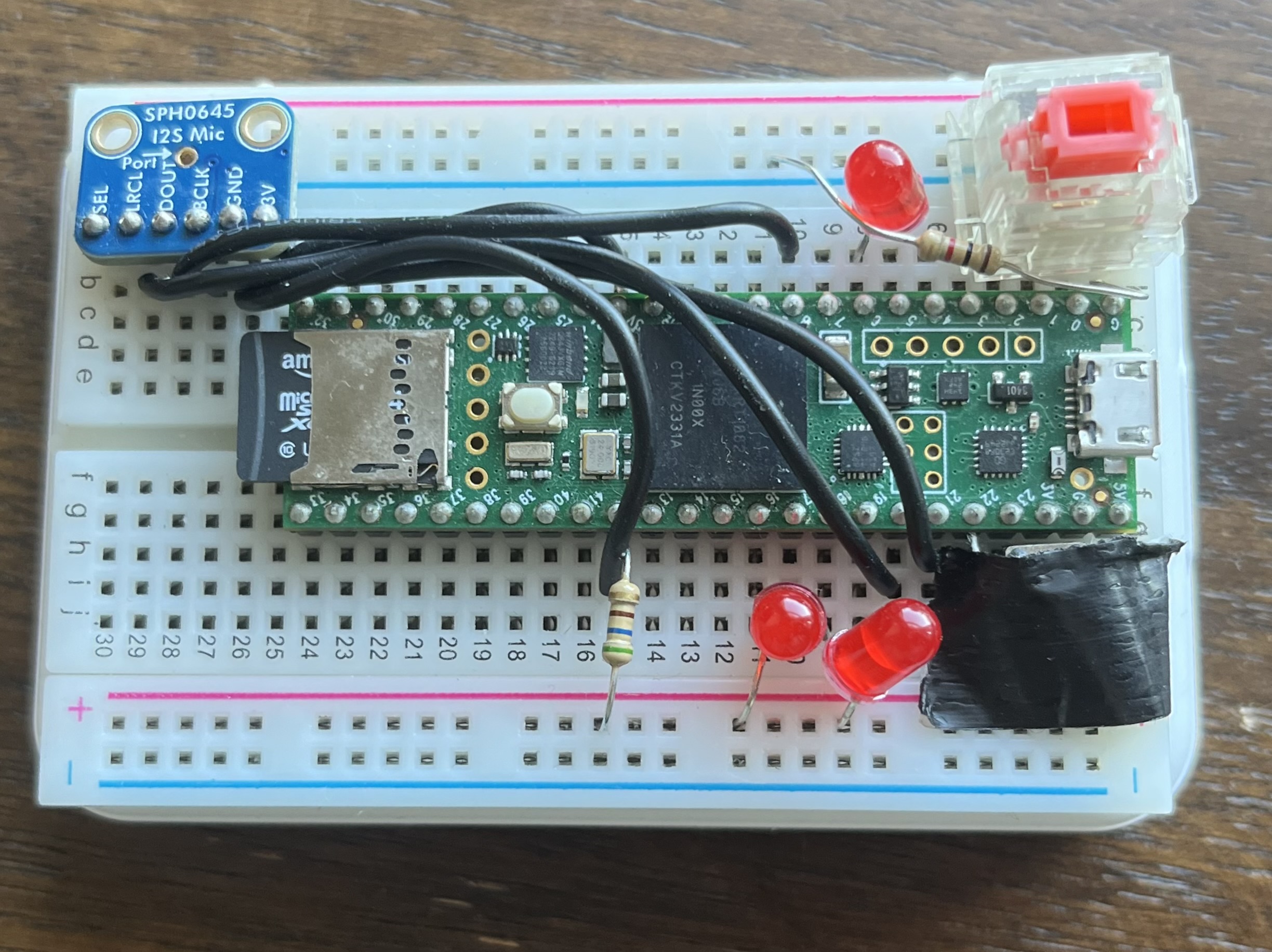

The Teensy 4.1 has an SD card. I built a program for data collection that records WAV files onto the SD card. The device has two buttons: one for starting the recording (the black one with tape over it), and another (red mechanical keyboard switch) for holding during a skateboard sound. The data collector produces four files per audio recording: an audio file, a labels file with the beginning and ends of half-second chunks, a helper file with when the red button was pressed, and a file of feature vectors for each half-second of audio (code pointer).

Feature Extraction

I had to choose a method of feature extraction that would run efficiently on the Teensy. I did all the feature extraction/vectorization of audio on the Teensy even for training. This locked me into a certain set of features, but it made it far easier to know that my features were being generated the same between training and deployment.

I needed to generate vectors for half-second chunks. Buffering up a half-second of audio and running an FFT on that isn’t feasible due to memory constraints on the Teensy. Instead, smaller frames of audio are taken and aggregated together. Frames are 1764 samples long and overlap by 882 samples with their neighbors. This means there are 25 frames in a half-second chunk of audio.

Each frame is vectorized when it is received via FFT to compute v_real and v_imag of size 2048 (power of two above 1764). The sample rate is 44.1 kHz, meaning the max frequency observed by FFT is 22.05 kHz. The result in v_real is distributed evenly in the frequency domain up to half the sample rate. I bin that frequency into ten logarithmically scaled bins (code pointer).

Two more features are added onto the vector. They are the root mean squared energy and the standard deviation of the root mean squared energy computed here. Thus each frame has a vector of length 12.

After 25 frames are collected, they are aggregated into a dimension 33 vector as follows (code pointer). For each frequency bucket, the maximum of that bucket, the standard deviation of that bucket, and the mean of that bucket across the 25 frames are included. Additionally, the mean root mean squared energy and standard deviations of root mean squared energy across the 25 frames are included. Another feature, the “sum delta energies,” captures the L1 norm of variation in energy across frames, which may perform better because the skate pop sounds are sparse.

Data Labeling

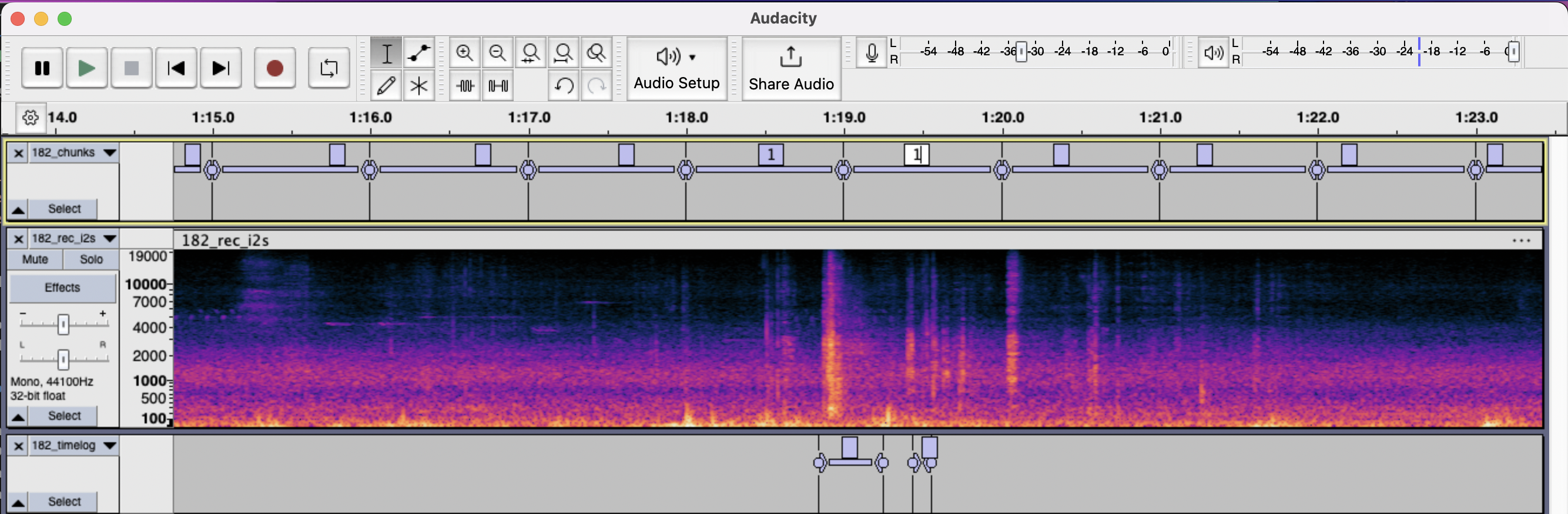

Labeling solely requires marking the labels to 1 on the sections of audio where there are skateboard sounds. I used Audacity for this.

Training

Feature vectors and labels are created in previous steps and maintained in a SQLite database. Training requires loading these vectors and labels, normalizing, and running backpropagation on the vectors for many epochs. Since there are far more 0 labels than 1 labels in the training dataset, I chose to use cross-entropy loss. The network has two hidden layers of 64 neurons and an output layer of two neurons where the higher probability neuron determines the predicted layer.

Deploying the Model

I recreated the model in C++ on the device via exporting the weights to a .h file that gets deployed onto the Teensy. I wrote an implementation of a forward pass function on the Teensy as well.

Here’s it in action trained on me tapping my pen: